85. Each of the operations of the skill requires the utmost attention in order to give oneself the perfection and safety which are necessary for the conservation of life. In what I have written, I have tried to clarify the doctrine of compasses, formations of the principal attacks or movements of the arm and sabre, and the removals of the first class. Order now demands that I should treat about the defensive guards, of the execution of the attacks and defenses, as was as of the variations that support each of the first order removals, and that give a greater degree of appreciability to the handling of this weapon.

86. The doctrine of defense is so united with that of offense that it cannot be known without perfecting both but, since they have equal utility, I will take the greater interest in that which one may execute with possible perfection. I will begin with the explanation of the guards, because these are the dispositive operations of combat. All of the removals of the first order, accompanied by the defensive stance, I call guards. Guards are differentiated from removals in that these have been executed to frustrate the intended offense, and those always precede the offense, so they are called guards and not removals, and that, covering certain planes they uncover others that can be directed toward the enemy. But as you know of advancing the points* that the enemy can attack on these guards, it is not difficult to accompany their movements with the removal. Therefore, have a great attention in taking them with the utmost promptness and without missing the circumstances I have tried to teach of the removals in the second chapter of the second part.

* What I call a point is any uncovered part to which you can address the offense.

The language in this section gets a little heavy, but Frias gives us some interesting terms and definitions here. Basically, point is more or less an exposed target in an open line. If they can hit it without interacting with my weapon, it’s a point. A removal is when my opponent attacks and I move the sword to a pre-defined position to counter their attack. The same positions as the removals are guards if I move to them in order to pre-empt an attack. Frias doesn’t clarify whether removal and parry share the same meaning.

87. I have already noted that all combat must be preceded by the choice of distance (§ 50), but I think it conducive to remind you here that this operation follows from the steps (§§ 21 and 22). Assume already that these circumstances enter into the matters of this chapter and so, when no mention is made of any distance or stance, you should suppose that all of the guards and attacks have been written.

Thrust of Fourth on the Guard of Third

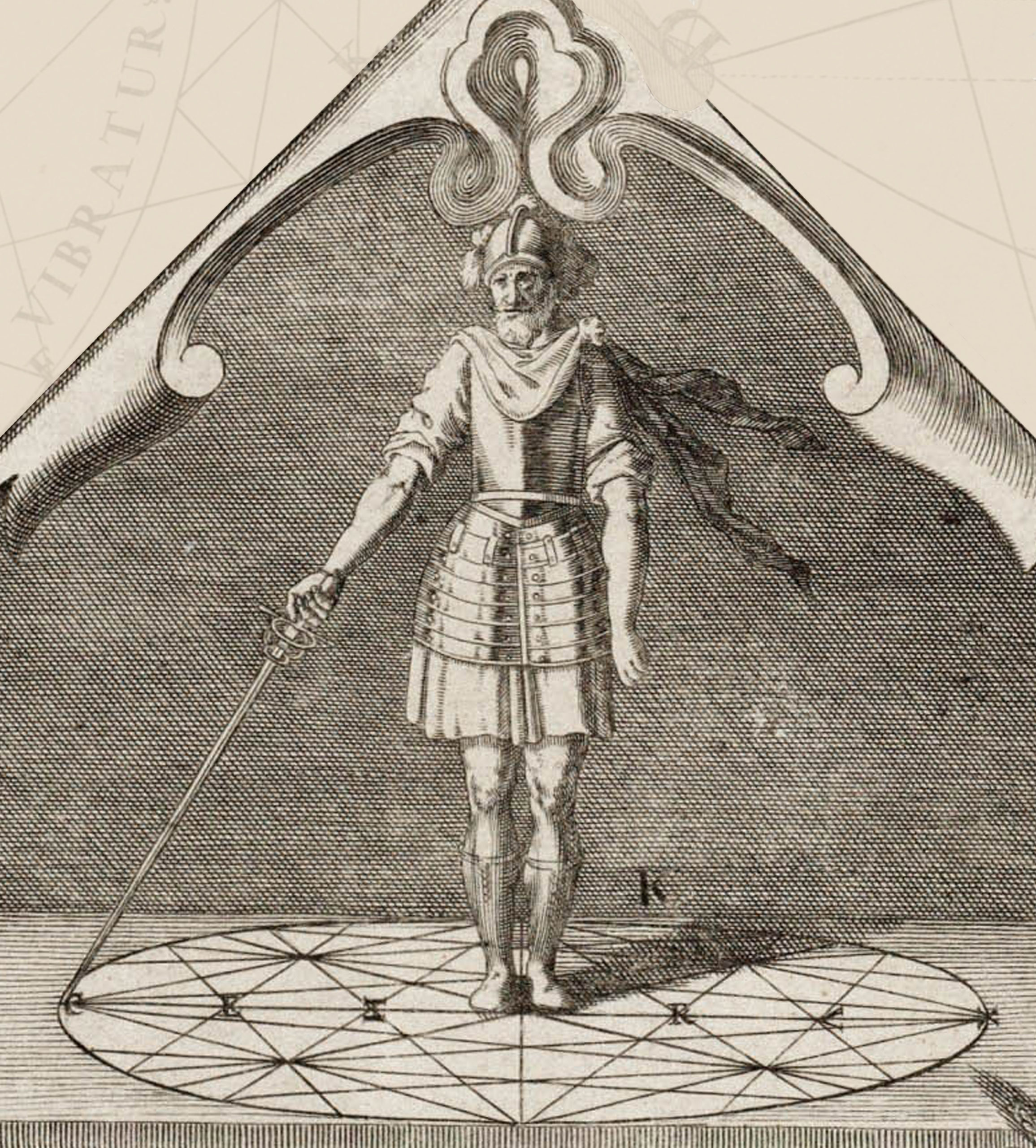

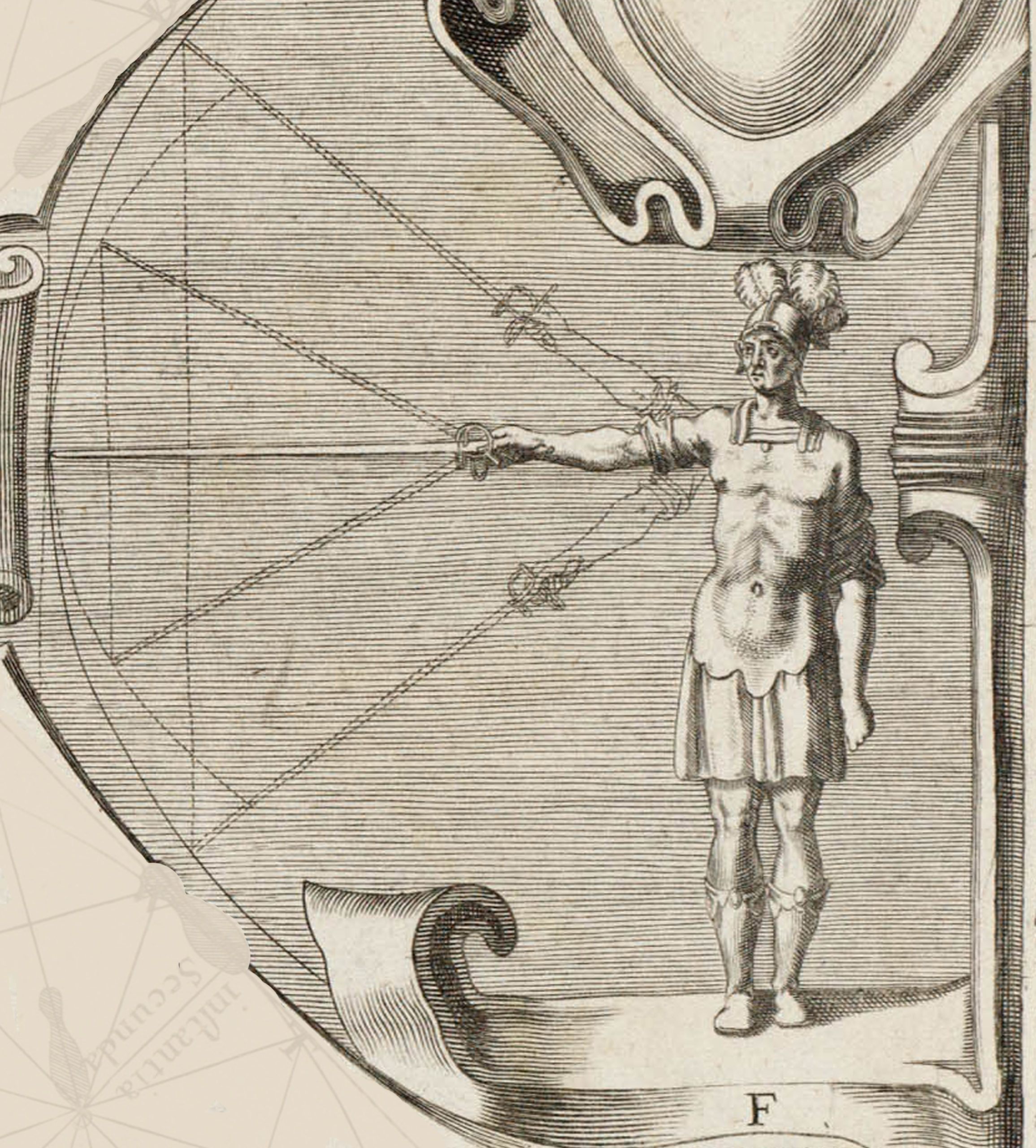

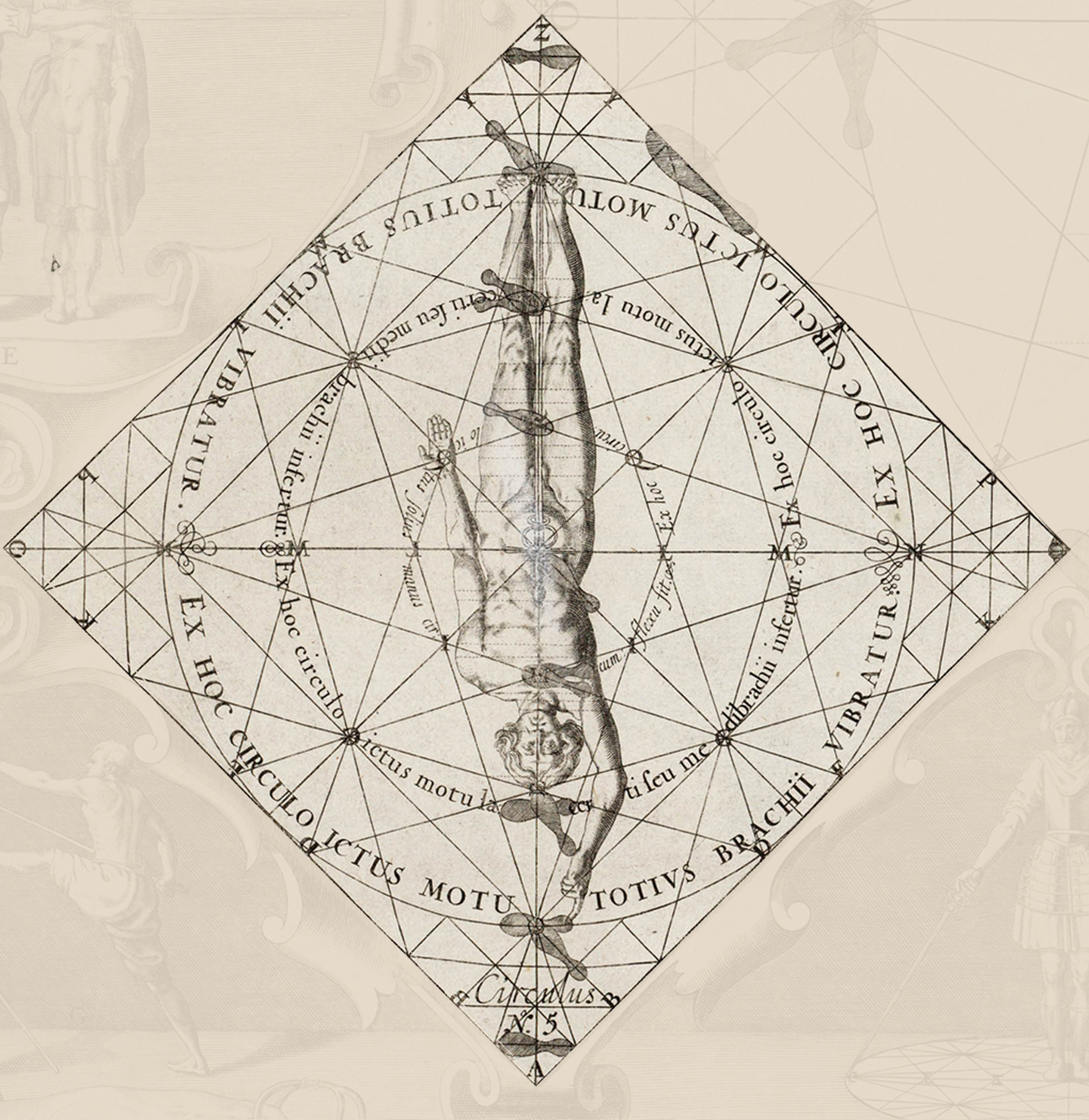

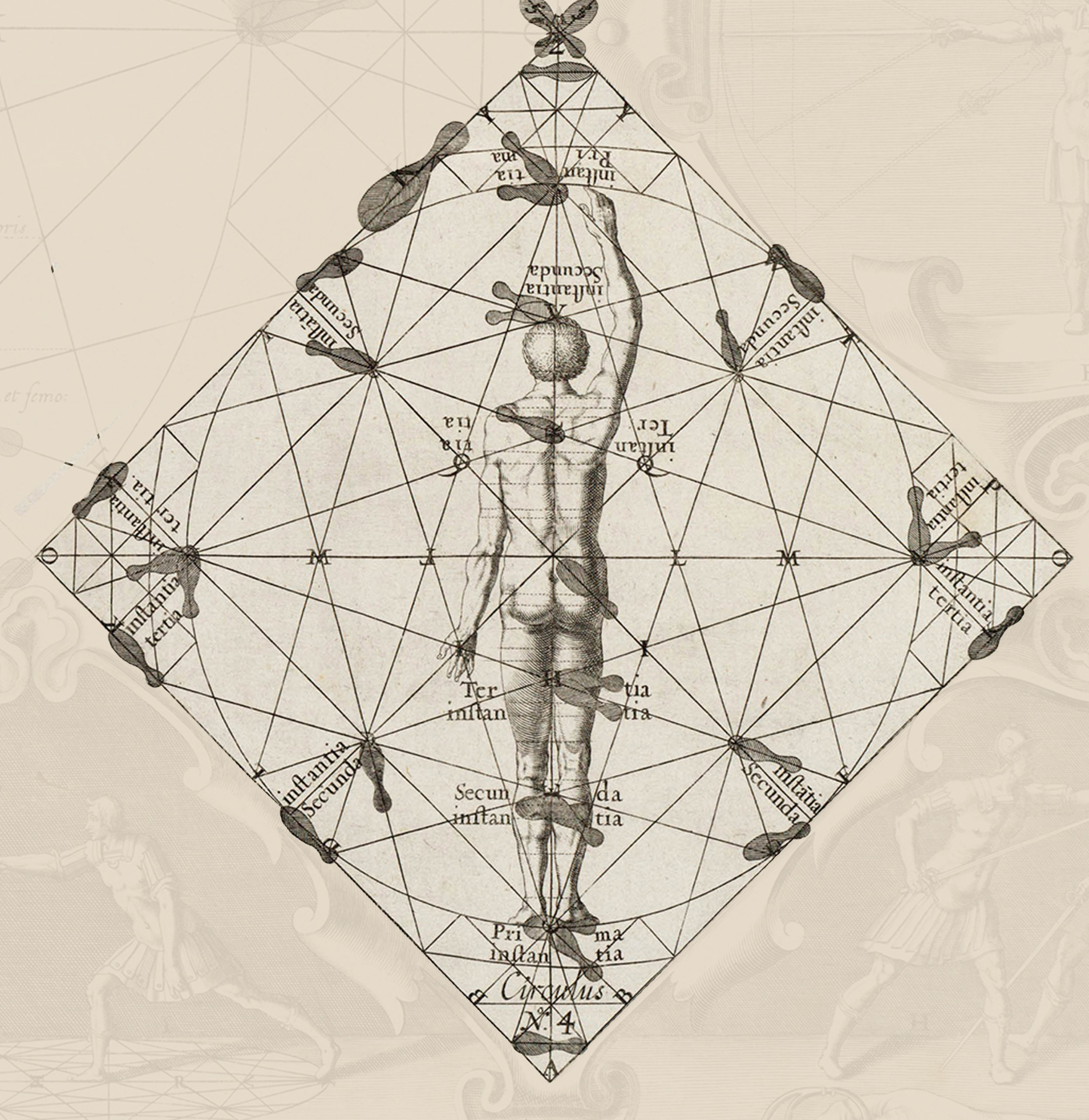

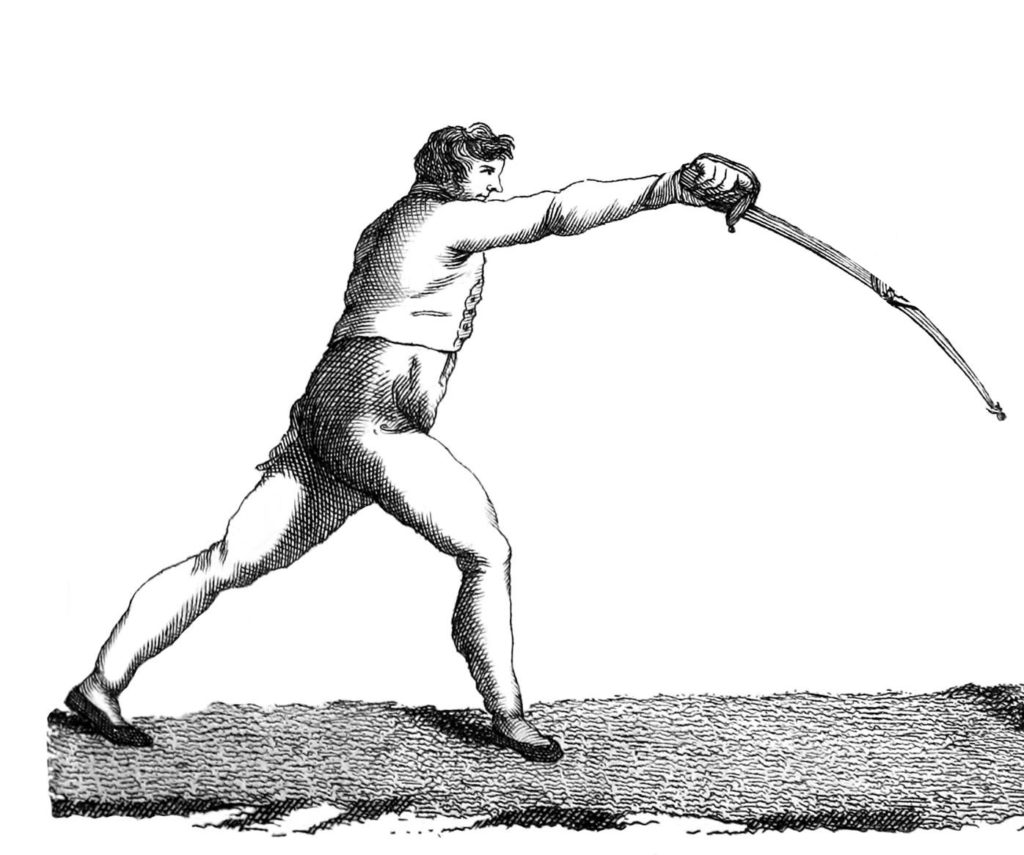

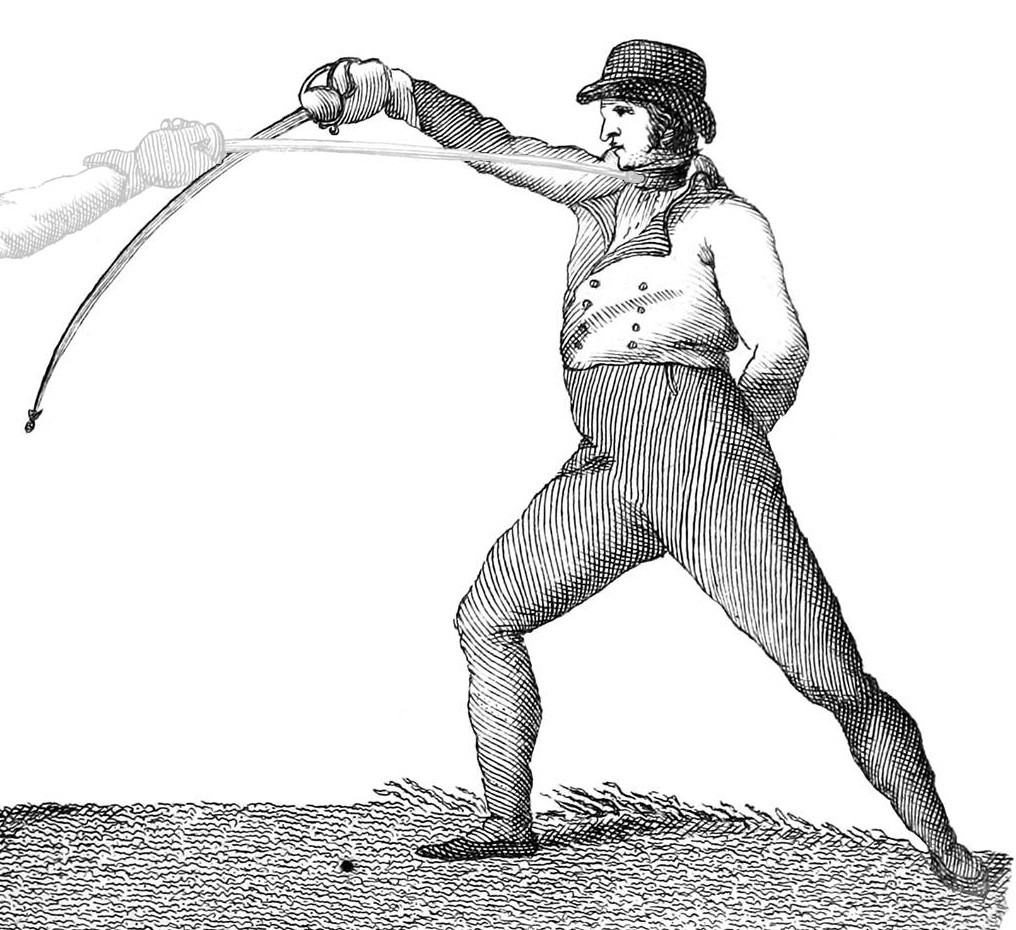

88. Take the guard of third to make the removal as explained (§§ 81 and 82). From this arrangement, the attacker will free the point of his sabre from the common guard, with only the wrist, to the inside and, turning his hand fully into fourth position, will direct a thrust to the chest, immediately at this point, accompanying it with a deep step very rapidly, and with the opposition of the hand necessary to cover the left vertical, the arm and sword at the height dictated (§ 60), movement of profile, and the whole body in the arrangement represented in plate 4, figure 6, letter A. This is the operation called the thrust of fourth.

89. Whether or not the thrust is made, the necessary removal must be thrown immediately without disengaging the sabre and covering the place that is occupied by the point of the contrary sabre. With this will come the knowledge that it is necessary to always reply by doing the removal with which the enemy avoids the attack you threw. Therefore, have this as a general rule, since I will be careful to announce the variations that it admits opportunely.

90. The recovery is nothing other than undoing the step that accompanied the wound and, just as this begins with the balance forward, in the recovery, begin by throwing the body over the left leg and pushing with the right, that was used for the offense. If the enemy responds to the offense with another, the retreat will be in a spanish step in one or two times, and with this catch the attack prepared to defend with balance, withdrawing, jumping back, etc.

91. Remove this thrust with the parry of fourth, executed in the moment the offender has freed his point. The arm, being without being bent must save some flexibility that cannot be given without slackening the joint of the blood. (Plate 4, Figure 6, Letter B).

Points That are Uncovered on the Parry of Fourth

92. The first point that is uncovered from the constraint of fourth is the thrust in third; second, the counter-edge blow to the wrist*; third, the edge blow to the thigh; fourth, half-reverse; fifth, the vertical cut to the arm; sixth and seventh, vertical or diagonal cut to the head. By the point of the sabre, first, the half cut; second and third, the vertical or diagonal reverse to the head, fourth, the diagonal reverse to anywhere along the lines of the right side.

*The counter-edge blow to the wrist, the edge blow of the same, and the vertical to the arm that follow consist of fewer movements than the thrust of third, which I put in first place, but as blows of the point are in better condition than those of the cut, I prefer thrusts to cuts.

Frias’ footnote gives us some very interesting information. First, it confirms his bias in favor of thrusts. Second, however, it tells us that his ordering, rather than being arbitrary, is both sequential and preferential.

Also of note in this paragraph is his use of the feminine ataja which I have rendered as “constraint.” This is one of the few times that any conjugation of the word atajo, so popular in earlier works of Destreza, appears in this treatise.

Thrust of Third on the Guard of Fourth

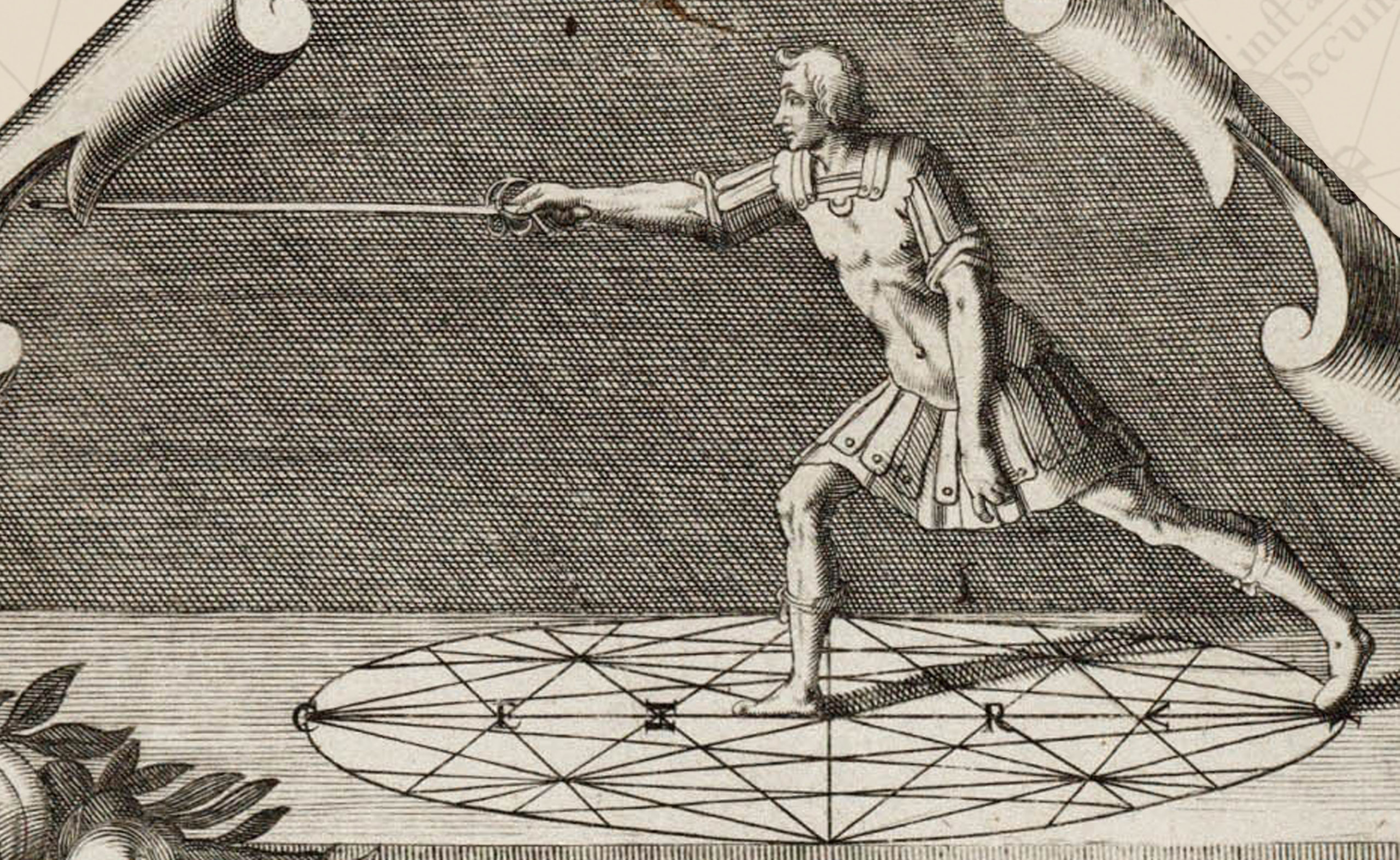

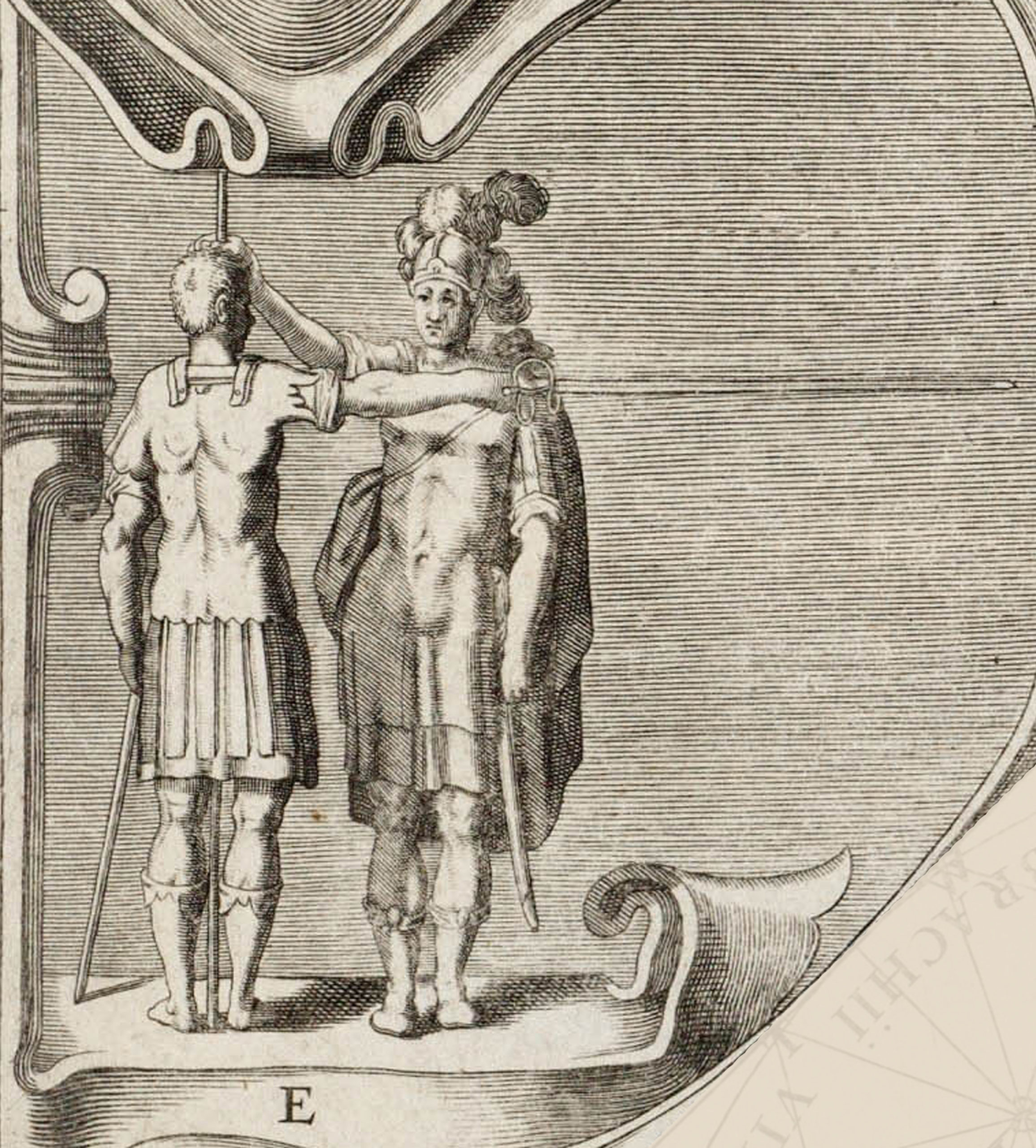

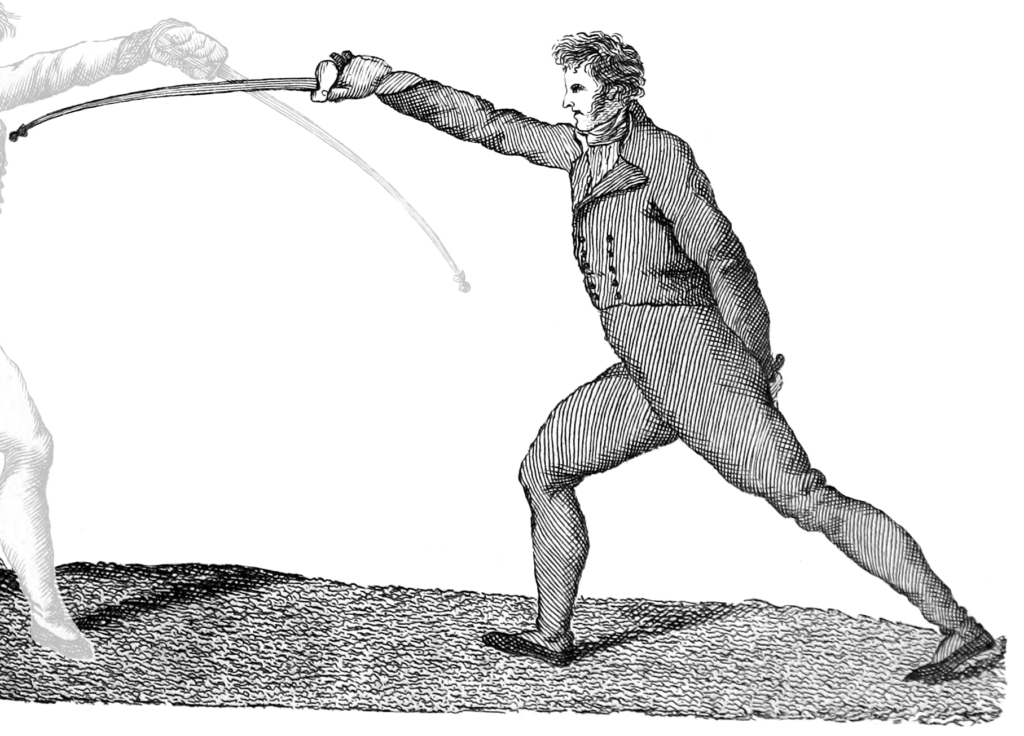

94. Take your opponent’s weapon with the guard of fourth as has been said (§ 80). In virtue of this, the attacker will free a thrust of third, accompanied by a deep step, turning their hand to third when it is possible, and direct the wound to the base of the enemy’s right arm. (Plate 4, Figure 7, Letter C). This is named the thrust in third, which will be followed by a quick recovery or retreat as I said in the previous shot.

The plate Frias references shows the point directed downward instead of toward the shoulder (how I am interpreting “base of the enemy’s right arm”). This is because, in that plate, the thrust has already been parried downward and to the side.

95. To avoid this offense, bear the greatest attention to the movements of the enemy and, as his point comes free and he begins to step deeply with the offense, turn the hand to the half-third position without bending the arm, and walk your sabre into place so that the guard covers the right vertical, the point is at the height of the contrary’s eyes, and on their left vertical, thus you will have completed the parry of third (Plate 4, Figure 7, Letter D)

Points that are Uncovered on the Parry of Third

96. Below the sabre, points are uncovered for the thrust of fourth, the false edge blow to the wrist or below the arm, thrust in second between the weapons, the diagonal revers from the right hip to the left shoulder, and the reverse to the knee. By the point of the sabre, the half reverse to the face, the vertical cut to the head, and the diagonal to any of the lines on the left side.

Thrust of First on the Guard of Fifth

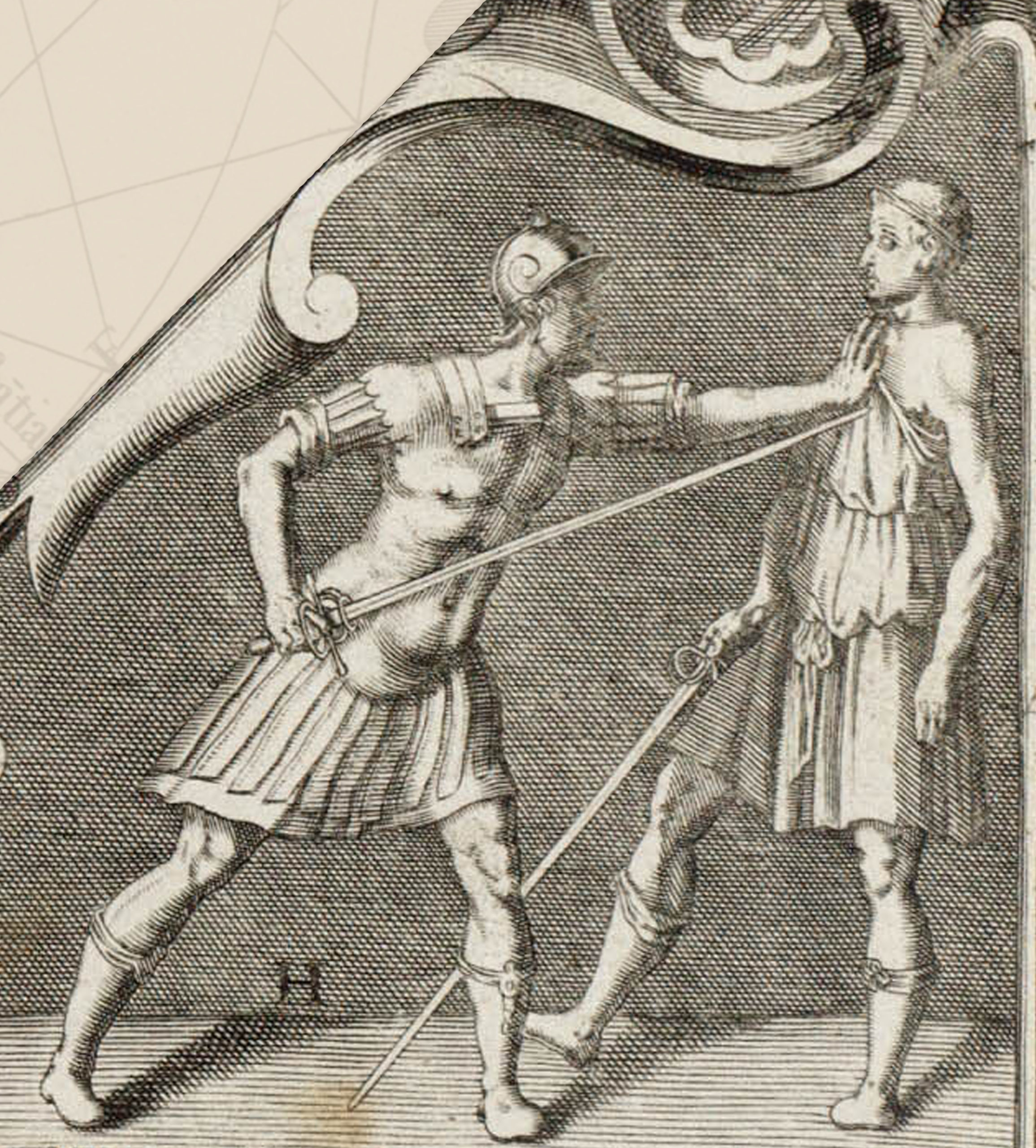

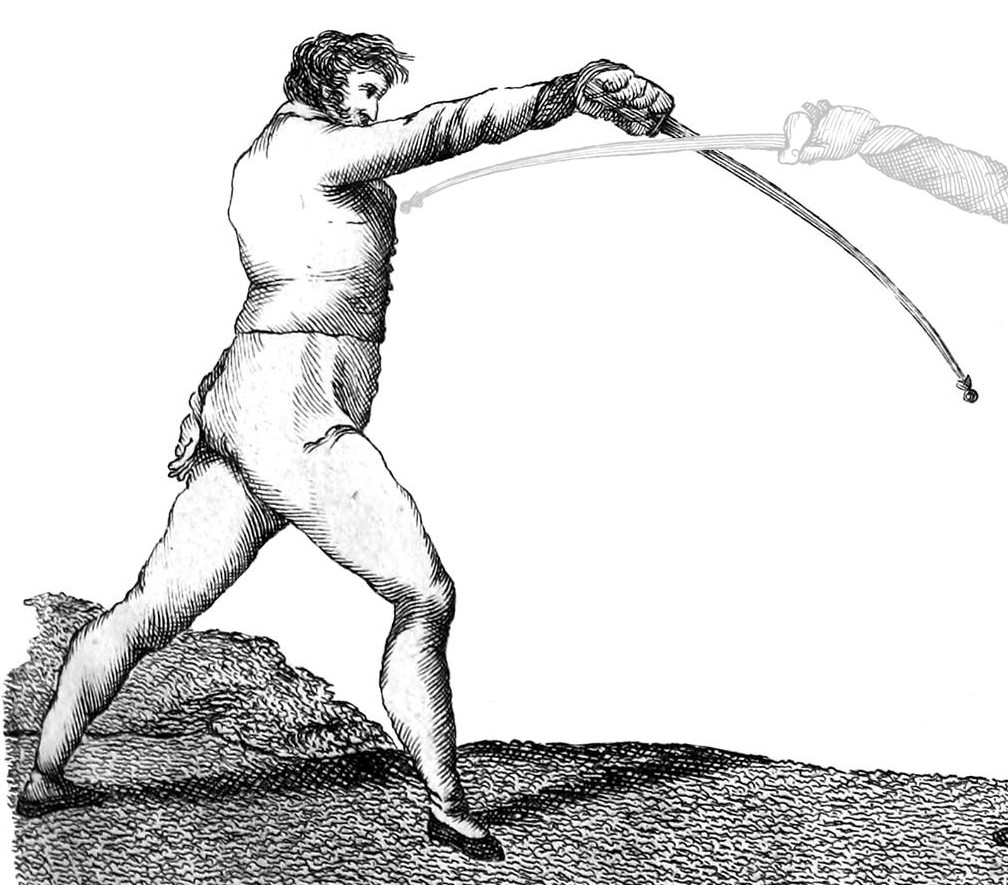

97. The one who is in the common guard and offensive stance, seeing that his contrary opposes in the guard of fifth (§ 84), should immediately turn his hand to fourth, freeing the point above the enemy’s sabre and, directing it to the right breast, opposing strong to weak and dispatch with the utmost violence, stepping deeply, a thrust to that point (Plate 5, Figure 8, Letter A) which, whether or not it succeeds, will quickly be recovered in the removal of sixth. This offense is called the thrust in first with the hand in fourth.

98. It is necessary, to evade this blow, that the one who awaits it observing the moment the contrary frees, makes their arm and weapon walk by the horizontal planes that they are in and, without varying the third position, cover the left vertical, making a third of the point of their sabre go outside of the right vertical of their opponent. With that, they will have done the removal of sixth (Plate 5, Figure 8, Letter B).

Points that are Uncovered from the Removal of Sixth

99. In this removal are uncovered the thrust in second, vertical reverse to the arm, and diagonal reverse to all of the lines on the right side.

Thrust of Second on the Guard of Sixth

100. On this guard (§ 83), the thrust of second is thrown and, in conformity with the principles, turn your hand to third, free the point above your enemy’s sabre and, extending the arm as soon as possible, raise the guard to the height of the superior plane, and direct a thrust to the right breast, stepping deeply. This is called second (Plate 5, Figure 9, Letter C). Take care not to delay the recovery and the removal of fifth.

101. The parry of fifth serves to liberate you from this wound, but it is necessary, immediately when the contrary frees the point, to walk the arm and sword through the horizontal planes they are in, until you bring the guard in line with the right ear, a third of the point outside of the enemy’s left vertical, and the edge facing up a little diagonally to the outside (Plate 5, Figure 9, Letter D).

Points that are uncovered on the Parry of Fifth

102. The one of fifth uncovers points for the thrust of first, and all of the diagonal cuts to the left side, but, if you do an open removal, it will also give the vertical to the arm, shoulder, or head. These same can be thrown on a good removal, if the offender leaves the line of the diameter on the right side, since they are the same distance from the enemy’s point, by virtue of the opening movement of the removal. Thus it is a consequence of the step chosen by the combatant with the same design.